Introduction

The Septuagint or LXX, is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Initially, the first five books of Moses, (also called the Torah, the Pentateuch, and sometimes the Law) in about 250 BC and then in the following years, the rest of the Hebrew Bible known as the Masoretic Text which is also the Christian Old Testament.

Its name comes by way of the Letter of Aristeas (explained later) which states that 72 Jewish priests translated the first five books of the Bible. The 72 was rounded to 70 hence the Roman numerals LXX. The name Septuagint is derived from the Latin Septuaginta meaning seventy and was first used by Augustine of Hippo.

When addressing this topic, three questions arise. Why translation into Greek? Why the Hebrew Bible? And what initiated the translation?

Let us address these questions in order.

Why the translation into Greek?

After Alexandria the Great conquered the then known world and after his death, his generals divided his empire amongst themselves. Ptolemy took Egypt and declared himself Pharoah and Ptolemy I. By the time his son Ptolemy II came to be Pharoah, the Greek language was functionally the official language of both Upper and Lower Egypt.[1]

So, the answer to the question of why Greek, is that it was the language the people living in Egypt, spoke.

Why the Hebrew Bible?

Egypt features prominently in the history of God’s chosen people. Abraham went to Egypt to obtain relief from the drought that swept Canaan. Isaac did similarly and so did his son Jacob. However, the descendants of Jacob’s family never returned and became slaves to their Egyptian taskmasters. After 400 years God sent Moses to bring them out into the land He promised them, Canaan. This happened in 1446 BC (1 Kings 6:1).

The Jewish community at Elephantine, an island in the Nile River, was probably founded as a military installation in about 650 BC. during Judean king Manasseh’s reign.[2]

When Nebuchadnezzar took the Jews into captivity in Babylon after he destroyed Jerusalem in 586 BC, he left some back at Jerusalem. After a short time, these people emigrated to Egypt (Jeremiah chapters 40 to 43).

The Jewish historian Flavious Josephus reported that Pharaoh Ptolemy I (323-285 BC) took thousands of Jewish prisoners of war back to Egypt, after his victory over Judea and Samaria in the late fourth century BC. And other Jews emigrated voluntarily to take advantage of economic opportunities due to the excellence of the land. As well, Josephus commented that the size of the Jewish population in Alexandria was second only to Jerusalem.[3]

As a result of these migrations, there was a preponderance of Jews living in Egypt.

The many Jews who were participating in Greek society, meant that they could not only speak Greek fluently but could read and write it as well. So, their scriptures in Greek was to be to their great advantage.

What initiated the translation?

The story of the origin of the LXX is told in the Letter of Aristeas, so called because it was a letter addressed from Aristeas of Marmora to his brother Philocrates. It deals primarily with the reason the Greek translation of the Hebrew Law was created, as well as the people and processes involved. The letter’s author claimed to be a courtier of Ptolemy II.

The story of the origin of the LXX is told in the Letter of Aristeas, so called because it was a letter addressed from Aristeas of Marmora to his brother Philocrates. It deals primarily with the reason the Greek translation of the Hebrew Law was created, as well as the people and processes involved. The letter’s author claimed to be a courtier of Ptolemy II.

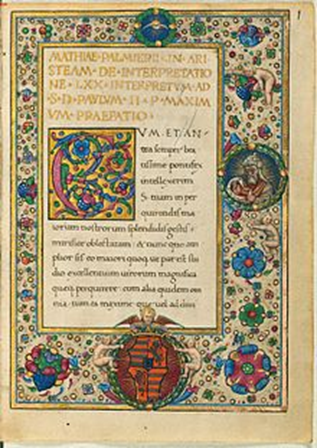

Over twenty copies of the letter are known to survive, dating from the 11th to the 15th century. The accompanying image shows a Latin translation, with a portrait of Ptolemy II on the right. It is kept in the Bavarian State Library and dates to about 1480.

The letter is also mentioned and quoted in other ancient texts, most notably in Antiquities of the Jews by Josephus (about 93 AD), in Life of Moses by Philo of Alexandria (about AD 15), and in an excerpt from Aristobulus of Alexandria (160 BC) which is preserved in Praeparatio evangelica by Eusebius.[4]

It states that Ptolemy II king (Pharaoh of Egypt, 285-246 BC) wished to have a translation of the Jewish law for his famous library in Alexandria. At his request the high priest Eleazer of Jerusalem sent 72 men, six from each tribe to Egypt with a scroll of the Torah. In 72 days, they translated one section from this scroll and afterwards they decided on the wording together.[5]

The image is of the granite statue which depicts Ptolemy II in the traditional canon of ancient Egyptian art. It resides at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

The image is of the granite statue which depicts Ptolemy II in the traditional canon of ancient Egyptian art. It resides at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

What is the truth of the story? The Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary states: It is generally agreed that the Pentateuch was translated from Hebrew into Greek in Egypt around the time of Ptolemy II, about 280 BC. The rest of the Old Testament was translated into Greek by various scholars in various places during the following two centuries.[6]

As to what initiated the original translation, Lanier and Ross, both men lecture on the Septuagint at different universities, and after discussing the possible reasons for the translation, they have this to say in their book:[7]

Stepping back, we can see how unlikely it is that the Greek Pentateuch was prompted by a single identifiable factor either outside or inside early Hellenistic Judaism itself. The project was motivated by a number of interconnected needs, opportunities and desires in and around the Jewish community.

On the one hand, given the relationship between the Ptolemaic monarchy and the Jewish community, we should not rule out some manner of external support for the translation initiative, even if it was indirect. Any such support was probably not as grandiose as the Letter of Aristeas suggests. But the time and physical resources needed to complete the process would have involved considerable financial burdens.

The translation of the whole Hebrew Bible was not completed until about the first century AD. During this time, work was done on revising the translations that had been completed to improve the accuracy, style, and simplicity.

The final product

The final product comprises the entire Hebrew Bible written in Greek plus several non-canonical Hebrew books; called the apocrypha. Examples are Tobit, Judith, Baruch, The Prayer of Manasseh, etc.

The final product comprises the entire Hebrew Bible written in Greek plus several non-canonical Hebrew books; called the apocrypha. Examples are Tobit, Judith, Baruch, The Prayer of Manasseh, etc.

As can be gleaned from the aforementioned, the Septuagint is a collection of translations. It is not a unified translation like something that would be produced by a committee. Like for example, a version of the Bible. For the ancients like the writers of the New Testament, it was not a single book that could be taken off the shelf, opened and read. But rather a collection of scrolls or a compilation of pages. Although, a complete book can be purchased today. One is shown.

The first English translation (which excluded the apocrypha) was by Charles Thomson’s in 1808, which was revised and enlarged by C. A. Muses in 1954 and published by the Falcon’s Wing Press.

Why is the Septuagint important?

It was important to the writers of the New Testament because they wrote in Greek, and because of the Septuagint, they could reference a Greek copy of the Hebrew scriptures.

At the time, the Jewish Bible did not exist as a single copy. During the sixth century BC, the Jewish state was scattered with most people going into exile in Babylon, some remained in Judea and others went to Egypt. As a result, up to five textual “families” of the Hebrew scriptures began to develop and these varied slightly from each other. The differences increased over the centuries as the Hebrew language evolved with respect to spelling, grammar, and sentence construction although there was no change in content or doctrine. By the first century AD, Jewish scholars became concerned about the state of their scriptures with numerous text types circulating, so they decided to use them to form one basic standard text family. These scholars and their text were the forerunner to the Masoretic family of texts of AD 500-1440.

The image is of the Leningrad codex, the oldest complete manuscript of the Masoretic Text. Acknowledgement, Wikimedia commons.

The image is of the Leningrad codex, the oldest complete manuscript of the Masoretic Text. Acknowledgement, Wikimedia commons.

The maintenance of the integrity of the Masoretic text was demonstrated by the Ancient Hebrew Research Center which compared Isaiah chapter 53 from the Masoretic text (AD 1,000) with the Dead Sea Scrolls (100 BC). Of the 166 Hebrew words that comprise the chapter, only 17 letters differ—10 letters are spelling differences, 4 are stylistic changes, and 3 letters are added for ‘light’ in verse 11[8].

By comparison, for each book of the Septuagint there was only one translation, except for Judges, Daniel, and the Minor Prophets.[9] This could be a further reason why the Septuagint was favored over the Masoretic text.

The influence of the Septuagint in the Bible

The name Psalms and Psalter come from the Septuagint. The traditional Hebrew title is tehillim

Archer and Chirichigno list 340 places where the New Testament cite the Septuagint but there are only 33 places where it cites from the Masoretic Text.[10]

Jesus quoted from the Septuagint. One clear example is recorded in Mark 7:6–7, where Jesus quotes Isaiah 29:13.

These people honor me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me. They worship me in vain; their teachings are merely human rules.

Further, the seven New Testament quotations of Leviticus 19:18 illustrate the point (Matthew 19:19, 22:39; Mark 12:31; Luke 10:27; Romans 13:19; Galatians 5:14; James 2:8). These five authors quote the passage, yet each quotation shares identical wording, and that wording matches the Septuagint exactly.[11]

For Paul to show the universality of sin as he does in Romans 3:12, he simply quotes Psalm 14:3 from the Septuagint and not the shorter Masoretic version which states:

They are all gone aside, they are all together become filthy: there is none that does good, no, not one.

Whereas the Septuagint[12] states:

They are all gone out of the way, they are together become good for nothing, there is none that does good, no not one. Their throat is an open sepulcher; with their tongues they have used deceit; the poison of asps is under their lips: whose mouth is full of cursing and bitterness; their feet are swift to shed blood: destruction and misery are in their ways; and the way of peace they have not known: there is no fear of God before their eyes.

To make the same point from the Masoretic text, Paul would have had to take sections from Psalms 5:9; 10:7; 36:1; 140:3 and Isaiah 59:7-9.

For an exhaustive analysis of the reliance of the New testament writers on the Septuagint, see; Steve Rudd, 300 Old Testament Quotations in the New testament, Septuagint vs Jewish Bible, https://www.bible.ca/manuscripts/List-of-300-Old-Testament-passage-quotes-in-New-Testament-Septuagint-Codex-Vaticanus-LXX-Masoretic-MT-Jewish-Tanakh-Bible.htm.

Conclusion

Galatians 4:4 tells us: But when the set time had fully come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law. Jesus came at a time when the good news, the gospel, could be spread far and wide. God used Alexander the Great to give the Mediterranean world a common language. Interestingly, the proceeding world power, the Persians, did not convert the world to Farsi and the power after the Greeks, the Romans, did not cause all the people to speak Latin. But in accordance with Galatians 4:4, the Romans did however, provide roads along which the gospel could be carried. They provided Roman law as well, and they established peace throughout the world. All of which facilitated the spread of the gospel.

It can be concluded that the Septuagint was important for preparing Greek speaking/writing Jews and God-fearing Gentiles for understanding the Old Testament and its fulfillment in Christ, as preached by the Apostles.

[1] Gregory R Lanier and William A Ross, The Septuagint What is it and Why it Matters, Crossway, 2021, page 43.[2] https://www.adefenceofthebible.com/2021/07/14/the-elephantine-papyri-confirm-the-books-of-ezra-and-nehemiah.

[3] Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 12:1-10. Taken from Paul L Maier, Josephus. The Essential Work, Kregel Publications, 1994, page 204.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_of_Aristeas.

[5] J D Douglas and Merrill C Tenny, Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary, Zondervan,2011, page 1,313.

[6] ibid

[7] Gregory R Lanier and William A Ross, The Septuagint What is it and Why it Matters, Crossway, 2021, page 55.

[8] https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/dss/great-isaiah-scroll-and-the-masoretic-text.htm.

[9] J D Douglas and Merrill C Tenny, Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary, Zondervan,2011, page 1,313.

[10] G. Archer and G. C. Chirichigno, Old Testament Quotations in the New Testament: A Complete Survey, 2005,

pages 25-32.

[11] Ibid, page 135.[12] Brenton’s Septuagint (LXX) – Holy Name KJV, http://qbible.com/brenton-septuagint/psalms/14.html.

1 Comment. Leave new

Boring as ever…Not asking a single question which frankly is pitiful!!!