Introduction

In the early 1500’s Erasmus of Rotterdam decided to correct the most commonly used form of the New Testament; Jerome’s’ Latin Vulgate, which Jerome had produced by translating from the Greek at the request of pope Damasus 1 in 382. In his translation, Jerome introduced errors, which under pinned the church’s hierarchical order and its doctrines. For example, in over twenty places Jerome translated the word metanoia as “do penance” instead of “repent.” Other errors support the Roman Catholic faith’s doctrine of Mary worship.

Jerome’s Vulgate (common language) was effectively the only Bible used from its inception, through the middle ages and up unto the revised translations of Erasmus; eleven hundred years later.

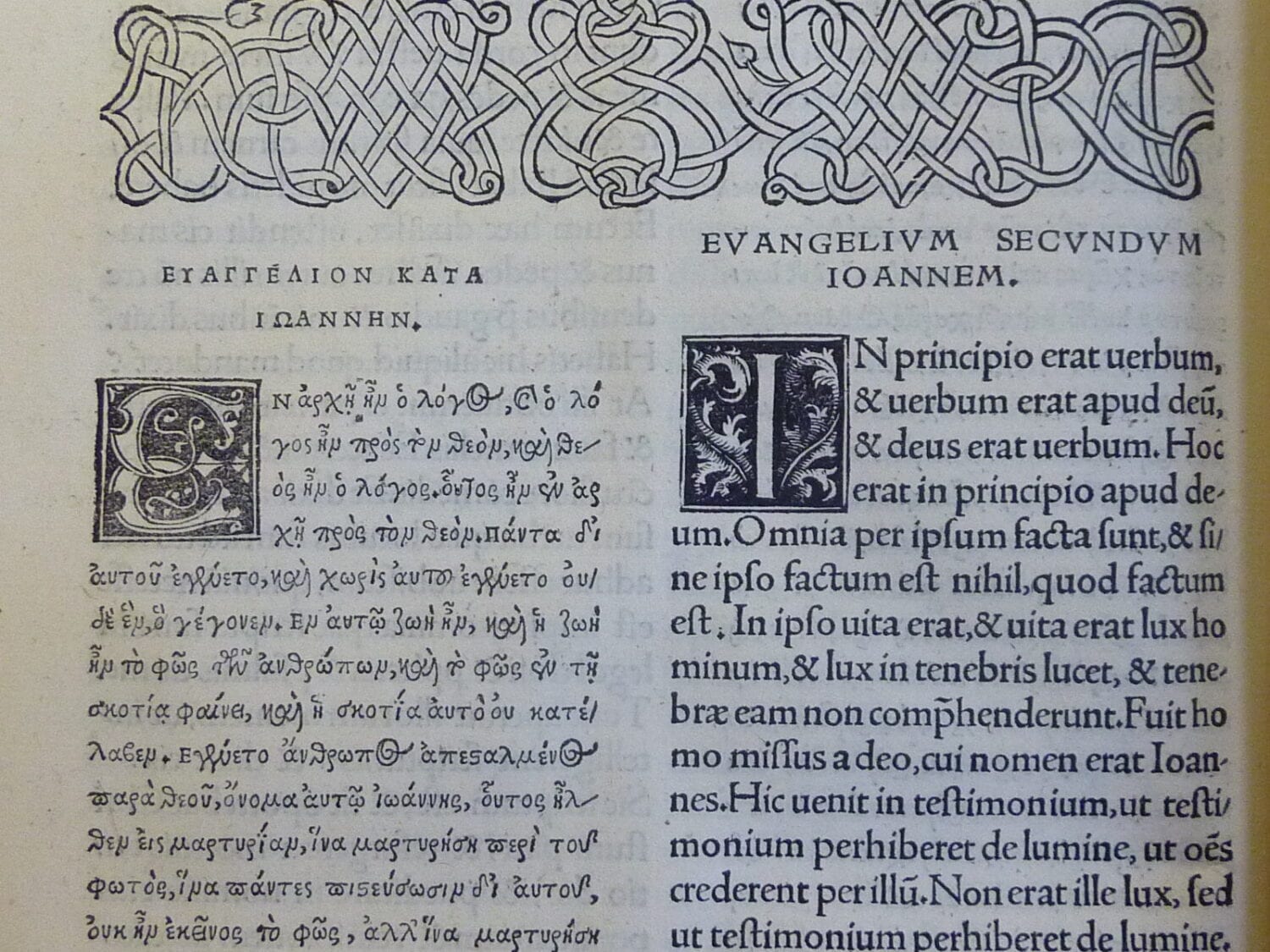

Erasmus set out to only translate into Latin, from the original Greek, but at the insistence of his printer, he also produced a Greek translation side by side with the Latin (pictured). Unfortunately, he had only seven incomplete Greek New Testament documents available to him to use and these were relatively recent from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries. There had been many copies of copies since the originals (autographs) and many small mistakes had accumulated. Even when he combined them, he was short of the last five verses of Revelation, so he back translated them from Jerome’s Latin.[1], [2] There were many errors due to the speed with which he prepared it and almost all of these were corrected in subsequent editions by Erasmus and others. His Greek translation became known as the Textus Receptus or Received Text and the first edition was published in 1516.

Erasmus set out to only translate into Latin, from the original Greek, but at the insistence of his printer, he also produced a Greek translation side by side with the Latin (pictured). Unfortunately, he had only seven incomplete Greek New Testament documents available to him to use and these were relatively recent from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries. There had been many copies of copies since the originals (autographs) and many small mistakes had accumulated. Even when he combined them, he was short of the last five verses of Revelation, so he back translated them from Jerome’s Latin.[1], [2] There were many errors due to the speed with which he prepared it and almost all of these were corrected in subsequent editions by Erasmus and others. His Greek translation became known as the Textus Receptus or Received Text and the first edition was published in 1516.

This scholarly work of Erasmus was of enormous value in improving the accuracy of the Holy Scriptures. The following Bibles were produced from the Textus Receptus; Luther’s German Bible (1522), Tyndale’s New Testament (1526), the Coverdale Bible (1535), the Matthew Bible (1537), the Great Bible (1540), the Geneva Bible (1560), the Bishops Bible (1568) and the King James Bible (1611). The New King James (1982) is predominantly from the Textus Receptus, although some earlier documents were used as well.

Constantin Tischendorf

Born Lobegott Friedrich Konstantin Von Tischendorf on January 18, 1815, in Lengefeld, Saxony, Germany. He began his scholarly career at the University of Leipzig in 1834 and took a special interest in the early writings of the New Testament. This gave him a desire to use the oldest manuscripts in order to compile the text of the New Testament as close to the original as possible. He came to realise that:

Born Lobegott Friedrich Konstantin Von Tischendorf on January 18, 1815, in Lengefeld, Saxony, Germany. He began his scholarly career at the University of Leipzig in 1834 and took a special interest in the early writings of the New Testament. This gave him a desire to use the oldest manuscripts in order to compile the text of the New Testament as close to the original as possible. He came to realise that:

The literary treasures that I have sought to explore have been drawn in most cases from the convents of the east, where for ages, the pens of industrious monks have copied the sacred writings, and collected manuscripts of all kinds. It therefore occurred to me whether it was not probable that in some recess of Greek or Coptic, Syrian or Armenian monasteries, there might be some precious manuscripts slumbering for ages in dust and darkness…[3]

So, in true Raiders of the Lost Ark fashion, he set off and in May 1844 at the age of 29, he came across the Convent of St Catherine at the foot of Mt Sinai (pictured); the oldest continually inhabited monastery in the world. It was constructed in 565. It has no doors and Tischendorf had to be lifted up to a window high off the ground to gain entrance and after being there some time, he commented in a book he later wrote:

So, in true Raiders of the Lost Ark fashion, he set off and in May 1844 at the age of 29, he came across the Convent of St Catherine at the foot of Mt Sinai (pictured); the oldest continually inhabited monastery in the world. It was constructed in 565. It has no doors and Tischendorf had to be lifted up to a window high off the ground to gain entrance and after being there some time, he commented in a book he later wrote:

..that I discovered the pearl of all my researches. In visiting the library of the monastery, in the month of May, 1844, I perceived in the middle of the Great Hall a large and wide basket full of old parchments; and the librarian, who was a man of information, told me that two heaps of papers like theses, moulded by time, had been committed to the flames.[4]

Tischendorf was only allowed to take 43 pages back to Leipzig, but he kept the location of his discovery a secret so that no other treasure seekers would go to the monastery. These pages were a part of a very ancient copy of the New Testament written in its original language of Greek. In 1853 he returned to the monastery in the hope of recovering more of the leaves he discovered before, but he found no trace of them. It was not until January 1859, and this time, with the financial support of the Russian government, that Tischendorf obtained many more of these New Testament pages and amazingly it was only on his last day at the monastery as he explained later:

…a bulky kind of volume, wrapped up in a red cloth… I unrolled the cover, and discovered, to my great surprise, not only those very fragments which, fifteen years before, I had taken out of the basket, but also parts of the Old Testament, and the New Testament complete.

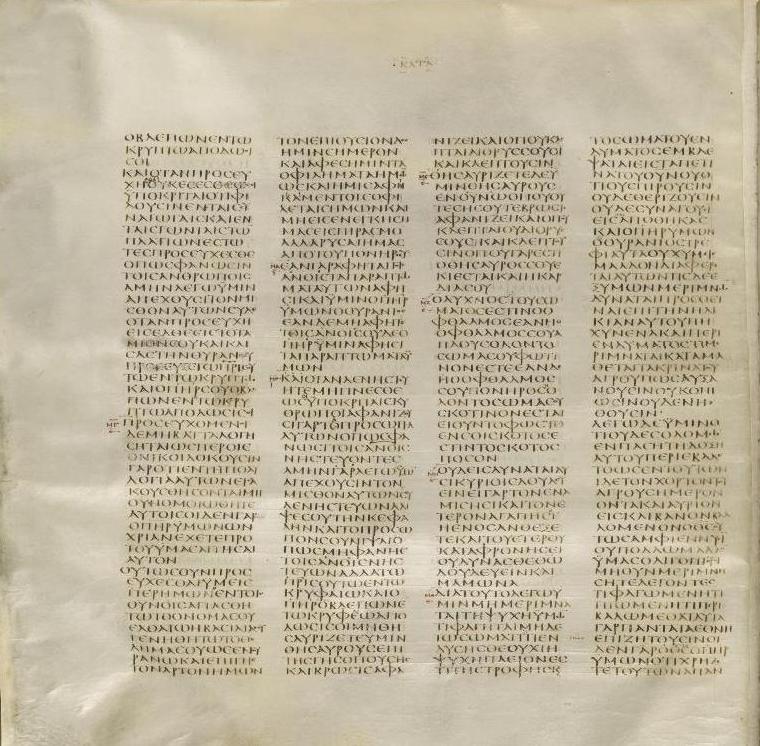

After intricate negotiations, Tischendorf purchased the treasure trove of documents for a sum of about $7,000 on behalf of the Russian Emperor; tsar Alexander Ⅱ. A part of Matthew’s gospel is pictured.[5] In 1862, he published a lavish reproduction of the codex, which after more editions became known as Codex Sinaiticus. Tischendorf had found the complete New Testament in its original language and dating to the second half of the fourth century; the oldest complete New Testament in existence and still considered to be the most valued.[6] The Codex Sinaiticus (pictured) and other equally ancient, but incomplete copies of the New Testament, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus have formed the bases of modern translations of the Bible.

After intricate negotiations, Tischendorf purchased the treasure trove of documents for a sum of about $7,000 on behalf of the Russian Emperor; tsar Alexander Ⅱ. A part of Matthew’s gospel is pictured.[5] In 1862, he published a lavish reproduction of the codex, which after more editions became known as Codex Sinaiticus. Tischendorf had found the complete New Testament in its original language and dating to the second half of the fourth century; the oldest complete New Testament in existence and still considered to be the most valued.[6] The Codex Sinaiticus (pictured) and other equally ancient, but incomplete copies of the New Testament, Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus have formed the bases of modern translations of the Bible.

The Russian Government sold the original Codex Sinaiticus to the British library in 1933 for £100,000. And that is where it resides today.

Addendum

In May 1975, during restoration work, the monks of Saint Catherine’s Monastery discovered a room beneath the St. George Chapel which contained many parchment fragments. Among these fragments were twelve complete leaves from the Sinaiticus.[7]

Conclusion

We can be very confident that the Bible we have today including those from the Textus Receptus, are very close to the original writings. There are small differences but theses do not affect its basic doctrine.

Moreover, the Bible is the most attested book of the ancient world with now over 5,700 copies of the Greek New Testament, more than 10,000 in Latin and more than 1,000 in other languages. The difference is stark when compared to Homer’s famous Illiad of 643 copies, the most of any other ancient document with its earliest manuscript copied 500 years after the original.[8]

The earliest piece of scripture in existence is a fragment of John’s gospel dated to AD 125-150. It contains Pilate’s famous question; What is truth? with Christ’s answer; Everyone that is of the truth hears my voice.[9]

[1] Roy E. Beacham and Kevin T. Bauder, One Bible Only? Examining the Exclusive Claims for the King James Bible, Kregel, Grand Rapids, 2001, page 82; Ron Rhodes, The Complete Guide to Bible Translations, Harvest House Publishers, Eugene Oregon, 2009, page 228.

[2] Erasmus seems to have inadvertently copied one of Jerome’s mistakes which refers to the “Book of life” in Revelation 22:19, but all Greek manuscripts refer to the “tree of life.”

[3] Echoes of Jesus does the New Testament Reflect What He Said?, Jonathan Clerke, Icefire Publishing, 2014, pages 133-134; citing: C. Tischendorf, Codex Sinaiticus: The Ancient Biblical Manuscript Now in the British Museum: Tischendorf’s Story and Argument Related by Himself. English trans., The Lutterworth Press, London, 1934, pages 16-17.

[4] Ibid, Tischendorf, page 23.

[5] The original documents were written in ancient Greek; Alexandrian text type, uncial lettering (all capital letters with no spacing or punctuation) in codex format (a book form as opposed to a scroll) and on vellum parchment (calf and/or sheep skins).

[6] Encyclopedia Britannica, online edition: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Konstantin-von-Tischendorf.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Sinaiticus.

[8] J. Sarfati, Creation, 2011, 33(1), page 33.

[9] Peter Masters, Heritage of Evidence in the British Museum, The Wakeman Trust, London, 2004, page 124.