To provide an answer to this question, let’s look at London in the early eighteenth century during a period known as the Gin Craze.

The Gin Craze

Between 1689 and 1697, the British government passed legislation preventing the importation of French brandy basically due to anti-French feelings with William of Orange occupying the English throne. To replace brandy, a drink which was mainly consumed by the upper class, people were offered gin and gin production was increased. In 1690, the monopoly of the London Guild of Distillers was broken, opening the market to gin distillation. Taxes on the distillation of spirits were reduced, and licences were removed, enabling distillers to have smaller, more simple workshops which involved the fermentation of grain with yeast. followed by the distillation of the liquor to increase its alcohol content over which there was no control.

In the sixteenth century gin was imported from Holland, and it was known as Jenever, with an alcohol content controlled to about 30% by volume. Its name morphed into “Geneva’ and even “Madam Geneva” when manufactured locally.

While this was happening, London was rapidly becoming more urbanised, but the industrial revolution which would provide much employment, many in cotton mills, had not commenced. The situation was made worse by the squalid living conditions in the slums. People were packed up to 10 per room, into dirty tenement houses. The only recreation or relief they could afford was gin. A most compelling reason why Londoners developed such a deep dependency on Madam Geneva, is that it was very cheap and that it provided an escape from the miseries of poverty. One woman told a magistrate that she drank it to keep out the wet and cold while she worked in her market stall. Otherwise, she claimed in her statement, she could not bear the long hours, the hard labour, and the awful weather. Her situation makes it easier to understand London’s Gin Craze.[1]

While this was happening, London was rapidly becoming more urbanised, but the industrial revolution which would provide much employment, many in cotton mills, had not commenced. The situation was made worse by the squalid living conditions in the slums. People were packed up to 10 per room, into dirty tenement houses. The only recreation or relief they could afford was gin. A most compelling reason why Londoners developed such a deep dependency on Madam Geneva, is that it was very cheap and that it provided an escape from the miseries of poverty. One woman told a magistrate that she drank it to keep out the wet and cold while she worked in her market stall. Otherwise, she claimed in her statement, she could not bear the long hours, the hard labour, and the awful weather. Her situation makes it easier to understand London’s Gin Craze.[1]

The picture is of an eighteenth-century gin bottle with London embossed on the top. It was found in a shipwreck off the coast of Finland.

The dividends of the Gin Craze

In a few decades, thousands upon thousands of low-rent gin shops saturated London in particular, exposing the working poor and the destitute to a spirit that was suddenly much cheaper, often cheaper than beer, and more available. Both production and consumption subsequently skyrocketed, going from roughly 500,000 gallons of gin in 1685 to 11 million gallons in 1733. In less than half a century, production in London had increased 2,100 percent.[2]

Many noted that the increase in production and use of gin played a direct role in the increase of crime, prostitution, madness, increase in deaths and falling birth rates. Between 1730 and 1749, 75% of all children born in London died before the age of five. The magistrate and writer, Henry Fielding, feared that to many people who were poor and living in slums, gin was readily available and quite cheap. In 1713 alone, London distillers had produced two million litters of raw alcohol for a population of roughly 600,000 people, with the finished product selling for a penny a dram (about a teaspoon full).

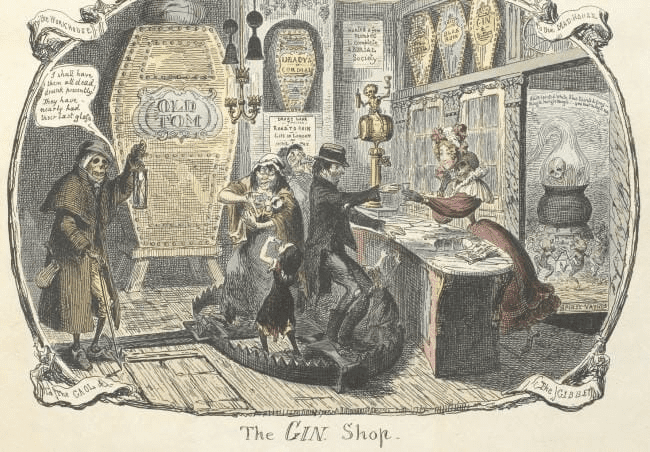

“The Gin Shop,” an anti-gin etching by artist George Cruikshank from 1829. Mothers, children, and men alike are pictured standing in the bear trap that represents the deadly effects of cheap, toxic gin.

By 1721, Middlesex magistrates were already decrying gin, as the principal cause of all the vice & debauchery committed among the inferior sort of people.

By 1730, an estimated 7,000 gin shops (and probably many more if one was somehow able to count the untold illegal drinking dens) were catering to the trade, with some 10 million gallons of the spirit distilled each year.

The depth of moral decline is revealed by the tragic case of Judith DeFour

Judith was born in 1701 and when she was 31 years old, she gave birth to a daughter, Mary. By the time Mary was two years old Judith did not have the means to support her and so she put Mary into a workhouse. Evidently, she stayed in contact with the child, because she was able to take Mary out for a few hours which was her right as her mother. One Saturday in late January 1734, Judith, and her friend, only known as “Sukey”, attended the workhouse to collect Mary. When they left, according to court records, the two women took the toddler into a nearby field, stripped her clothing from her, and tied a linen handkerchief around the child’s neck, to “keep it from crying”. Judith and Sukey then laid Mary in a ditch and abandoned her, taking the child’s clothes with them. They went back into town and sold the coat for a shilling and the petticoat and stockings for two groats. They then split the money between them and went out and spent it on a “Quartern of gin”.

Witnesses who worked with Judith stated the following day, that she had told them that she had done something that deserved Newgate, and then asked for money to buy food, which she was granted, yet she used it to buy more gin. Mary was found dead in the ditch where her mother had left her. Judith Defour was quickly apprehended, tried at the Old Bailey, found guilty of murder, and was executed in March 1731.[3]

In 1736 the Middlesex Magistrates complained:

It is with the deepest concern your committee observe the strong Inclination of the inferior Sort of People to these destructive Liquors, and how surprisingly this Infection has spread within these few Years … it is scarce possible for Persons in low Life to go anywhere or to be anywhere, without being drawn into taste, and, by Degrees, to like and approve of this pernicious Liquor.[4]

In 1738 Bishop Butler asserted that Christianity was treated as though it was now discovered to be fictitious…and nothing remained but to set it up as the subject of mirth and ridicule. His statement showed an inverse relationship between Christianity, measured by church attendance and gin consumption. As gin consumption increased, so did crime, but church attendance decreased.[5]

Around 1743 the Gin Craze reached its peak, with more than 18 million gallons of gin being consumed, and England was drinking 2.2 gallons (10 litres) of gin per person per year. As consumption levels increased, an organised campaign for more effective legislation began to emerge, led by the Bishop of Sodor and Man, Thomas Wilson, who, in 1736, had complained that gin produced a “drunken ungovernable set of people”.

By 1750 over a quarter of all residences in St Giles parish in London were gin shops, and most of these also operated as receivers of stolen goods and co-ordinating spots for prostitution.[6] Thomas Fielding, a social historian of the time, wrote about the ravages of the trade on what he termed the “inferior people” in his 1751 political pamphlet Enquiry into the causes of the late increase of Robbers:

A new kind of drunkenness, unknown to our ancestors, is lately sprung up among us, and which if not put a stop to, will infallibly destroy a great part of the inferior people. The drunkenness I here intend is … by this poison called Gin … the principal sustenance (if it may be so-called) of more than a hundred thousand people in this Metropolis.

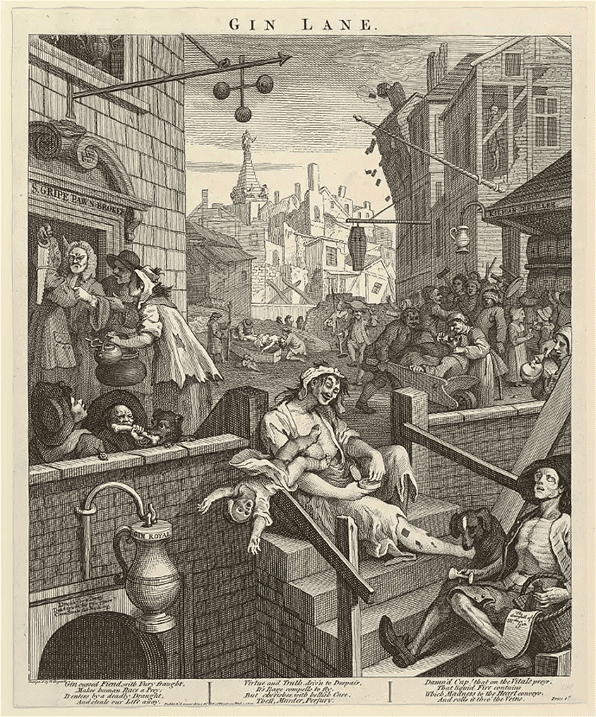

Gin Lane

No one captured London’s Gin Craze more confrontingly than artist William Hogarth. In his etching entitled Gin Lane, Hogarth depicted the devastation that gin had brought upon his fellow Londoners. The gin den in the foreground bids people to enter, with the promise that they can get “drunk for a penny, and dead drunk for twopence”.

To the right of the picture is a cadaverous man, his drinking cup in one hand and his gin bottle in the other. Above his head, two young girls can be seen taking a drink of gin, whilst a mother pours some down her infant’s throat. To the left is a boy who fights with a dog over a bone. Behind the boy, a carpenter is selling the tools of his trade to a pawnbroker so that he can afford more gin. In the background, a dead woman is being lifted into a coffin, her infant child left sitting on the ground beside her coffin. Next to them is a drunken man who in his crazed stupor has impaled a child on a spike, the child’s horrified mother is screaming at him, but he appears oblivious. In the upper right of the picture, we see a solitary figure hanging from the rafters in his garret, an apparent victim of suicide and of London’s Gin Craze. Most shockingly, the focus of the picture is a woman in the foreground, who, addled by gin and driven to prostitution by her habit — as evidenced by the syphilitic sores on her legs — lets her baby slip unheeded from her arms and plunge to its death in the stairwell of the gin cellar below. Half-naked, she has no concern for anything other than a pinch of snuff.

The end of the gin craze

London’s Gin Craze finally came to an end in 1751, when Parliament passed the Sales of Spirit Act of 1751. By this stage, the government had realized what a truly terrible toll London’s obsession with this cheap spirit was having on society. This Act was created because gin had been identified as the city’s main cause of laziness, prostitution, and crime.

Parliament and leaders of religion had tried twice before to curb London’s addiction to gin, once in 1729 and once in 1736, with Acts that raised taxes and brought in licensing fees for the production and sale of gin. However, these were dropped when the working classes started rioting in the streets of London.

The 1751 Gin Act brought in financial disincentives for the making and selling of gin and this time it proved to be a great disincentive for its production by small distillers. Its success is witnessed by the fact that the production of gin fell from 32,000,000 litres in 1751 to 19,300,000 litres in 1752, the lowest level for 20 years.[7] Fortunately, people took to tea drinking as a replacement for gin. Formerly a drink that only the wealthy could afford, the British East India Company’s imports of tea had quadrupled in the years spanning 1720 to 1750. By the 1760s, one observer noted that the poor were avid drinkers of tea; even beggars could be seen taking a cup of tea in the city’s laneways.

The 1751 Gin Act brought in financial disincentives for the making and selling of gin and this time it proved to be a great disincentive for its production by small distillers. Its success is witnessed by the fact that the production of gin fell from 32,000,000 litres in 1751 to 19,300,000 litres in 1752, the lowest level for 20 years.[7] Fortunately, people took to tea drinking as a replacement for gin. Formerly a drink that only the wealthy could afford, the British East India Company’s imports of tea had quadrupled in the years spanning 1720 to 1750. By the 1760s, one observer noted that the poor were avid drinkers of tea; even beggars could be seen taking a cup of tea in the city’s laneways.

England did recover its virtue.

The 1751 Gin Act made gin too expensive for the ordinary people to purchase and consequently, they had more money to buy the essentials of life. Three years before this act was pronounced, George Whitefield had given his life to Christ, and he began preaching the gospel with a fervency that had not been heard since the days of John Bunyan. In the very year that bishop Butler lamented the loss of Christian influence in England, the brothers John and Charles Wesley finally gave their lives to Christ and followed Whitefield’s footsteps. William Wilberforce the Christian politition, led the successful fight against slavery. One who helped him was John Newton, the slave trader who turned to God and wrote a hymn that is still sung today, Amazing Grace. Good government came by about by the way of William Pitt the Younger. English churches were full again. Britain had regained its moral compass.

Societies that have recovered from moral collapse.

There are two clear examples from scripture where the people rejected God and worshipped foreign gods just as the people of eighteenth-century England did. Gin was their god. Judah under the reigns of Hezekiah and his great grandson Josiah had the foreign objects of worship removed from the land and the temple restored. God blessed these kings’ actions and prosperity followed.

Can our Western society recover from its moral collapse?

Our western society is Christian based, the Magna Carta was written by the church in 1215, the Bible was the basis for the American Constitution and common law is based on the Ten Commandments; it has served us well. However, the fall of our society started in the 1960’s as shown by two US Supreme Court’s decisions:

- In 1962 The US Supreme Court removed this simple invocation to God before the children commenced their schoolwork:

Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee and beg Thy blessing upon us, our parents, our teachers and our country.

- In 1963 the US Supreme Court ruled that school-sponsored Bible reading and prayer be banned in all US public schools. This was brought about by atheist Madeline O’Hair Murray. She was later killed by one of her atheist’s friends, but the damage was done.

Many Western countries follow the US’s lead.

Since the mid-sixties there has been a dramatic increase in teenage pregnancies, drug use, suicides, children born out of wedlock and in many instances not knowing who their father is, and abortions which now is a government funded industry.

The attack on the Christian basis of our society has increased dramatically since the 1960’s and has focussed on what the Bible upholds.

God made them male and female (Genesis 1:27)

Our sex is hard-wired in every person. Males have an X and a Y chromosome and females have two X chromosomes in every one of the 17 trillion cells that comprise us. Yet children are now taught in their taxpayer funded government schools, that they can choose their gender. This has led to confusion and a wave of psychological disorders.

Abortion

The Bible says that God knitted us together in our mother’s womb (Psalm 139:13). There are almost one million babies aborted in the United States each year. In many cases because the child was inconvenient.

Homosexuality

The Bible clearly condemns this practise; Genesis 18:16-19:29, Leviticus 18:22, Leviticus 20:13, 1 Corinthians 6:9-11, Romans 1:26-32, 1 Timothy 1:9-11. Our society now celebrates it with “Gay Mardi Gras.” In some states in some countries, laws have been introduced that makes it a criminal offence to simply pray for those who want to get out of the practise.

Can our society recover from this moral collapse?

NO! Unfortunately, the above has now become endemic in our society. It is being pushed, by the mainstream media, all liberal governments, big business, and big sport. The Bible tells us of times like this;

Luke 17:28-29 It was the same in the days of Lot. People were eating and drinking, buying and selling, planting and building. But the day Lot left Sodom, fire and sulfur (brimstone) rained down from heaven and destroyed them all.

2 Timothy 3:1-5 But mark this: There will be terrible times in the last days. People will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, boastful, proud, abusive, disobedient to their parents, ungrateful, unholy, without love, unforgiving, slanderous, without self-control, brutal, not lovers of the good, treacherous, rash, conceited, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God—having a form of godliness but denying its power.

Conclusion

Unlike previous societies that have lost their way, there appears to be no turning back and we can only look to Christ’s return.

[1] https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/iminds/drug-gin-craze.pdf.[2] Jim Vorel, The Gin Craze: When 18th Century London Tried to Drink Itself to Death, https://www.pastemagazine.com/drink/alcohol-history/the-gin-craze-britain-1700s.

[3] https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/images.jsp?doc=173402270010.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gin_Craze.

[5] https://lexloiz.wordpress.com/tag/gin-craze. Quoting Arnold Dallimore, George Whitefield, Vol 1, Banner of Truth, page 31.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beer_Street_and_Gin_Lane, citing Gay, John (1986). Bryan Loughrey and T. O. Treadwell (ed.). The Beggar’s Opera. Penguin Classics.

ISBN 0-14-043220-5, page 14.

[7] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gin_Craze citing P Dillion, The Much Lamented Death of Madam Geneva the Eighteenth Century Gin Craze, ISBN 1-932112-25-1, 2004, page 263.