Introduction

Unlike later Egyptian pharaohs, the pharaoh of the exodus remains unnamed in the Bible. The likely reason for this is that Moses followed the standard Egyptian practice at that time. This meant referring to enemy kings by their titles only, while deliberately leaving them unnamed. Just who was the pharaoh of the exodus?

Much has been written about the identity of this man. It is a topic of debate amongst scholars and researchers. Some say it was under Thutmose III, others say Amenhotep II. Others believe it was Rameses II, Seti, or Seth, still others Akhenaton. Cecil B De Mille in his film Moses had Rameses II as pharaoh of the exodus and his assignment is supported by the Encyclopedia Britannia. A thorough examination of the Bible will supply the answer.

In order to answer the question, we need to know when the exodus took place?

The Bible tells us in 1 Kings 6:1

In the four hundred and eightieth year after the Israelites came out of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, the second month, he began to build the temple of the LORD.

So, what year was the fourth year of king Solomon’s reign? Synchronisation between certain events in the reigns of later Israelite kings and Syrian chronological records fix the fourth year of Solomon’s reign at 966 BC. If Israel’s exodus is placed 480 years prior to 966, it would have occurred in 1446 BC.[1]

This assignment is supported by two other biblical references.

Judges 11:26

For three hundred years Israel occupied Heshbon, Aroer, the surrounding settlements and all the towns along the Arnon. Why didn’t you retake them during that time?

Here Jephthah explains to the king of the Ammonites that they, Israel, had occupied the land for 300 years since they entered it after the exodus. Jephthah lived about 1100 BC. Add another 40 years of wandering gives a date for the exodus at about 1440 BC.

1 Chronicles 6, lists the sons of Levi which comprise 19 generations from the exodus to the construction of Solomon’s temple. This fits neatly with each generation being conceived at an average of 25 years. If for example, Rameses II who reigned in the thirteenth century was the pharaoh at the time of the exodus, each generation would have to have been conceived at an average age of twelve.

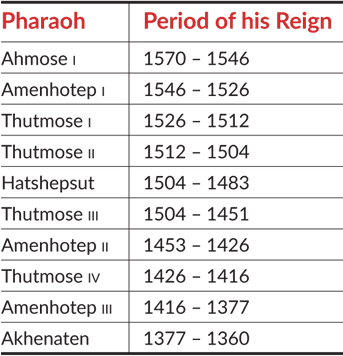

Is there a listing of pharaohs with their length of reigns?

Many kings ruled Egypt over almost three millennia of independent existence. Some pharaohs had up to five names and for a period of several years, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms one being Upper Egypt and the other Lower Egypt. This was during the Second Intermediate Period (1670 BC-1570 BC). So, constructing a chronological list of pharaohs is thwart with difficulty. Fortunately, in the third century BC, the Egyptian priest Manetho authored the Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt), a major chronological source for the reigns of the kings of ancient Egypt from Egyptian records.[2] This was most likely done at the request of the Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt at the time. The list written in Greek, and it contained the names, lengths of reigns, and prominent feats of all the kings. It was arranged by ruling houses or dynasties.[3] Only part of Manetho’s work has survived by way of references by later authors such as the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius (first century AD), Julius Africanus (third century AD) and Eusebius of Caesarea (third/fourth century AD).[4]

Manetho’s work has become accepted by most scholars and is used to provide the list of Egyptian pharaohs that are used today.

Which Pharaoh was on the throne in 1446 BC?

Although the dating of Egypt’s eighteenth kingdom has become much more refined, debate still exists between two opposing chronological frameworks. These are an earlier high chronology and a later low chronology. The difference between the two are only about two decades. Prof. Douglas Petrovich, argues persuasively for the higher and earlier chronology which is given here.[5]

It can be seen clearly using the biblical date of the exodus as being 1446 BC, that it was Amenhotep II who Moses confronted.

It can be seen clearly using the biblical date of the exodus as being 1446 BC, that it was Amenhotep II who Moses confronted.

Not only being pharaoh at the right time, but there are also two more requirements of the pharaoh of the exodus. His predecessor must have ruled for more than 40 years since the Bible states that Moses spent 40 years in Midian, and we are told that at the end of that time, the King of Egypt died (Exodus 2:23 and 4:19). The other requirement is that the exodus pharaoh’s first-born son must have died as a result of the tenth and last plague, and consequently, he could not have been the next pharaoh as was the custom. Amenhotep II’s predecessor was Thutmoses III who reigned for 47 years. Amenhotep’s successor was Thutmoses IV who was his second eldest son. His eldest son was Amenemhat, and he did not succeed him as pharaoh. Thus, both these conditions were met by Amenhotep II.

The first requirement was not met by Ramses II (also spelt Ramesses) and this rules him out as being the pharaoh of the exodus as well as him reigning in the third century BC. His predecessor was Seti I who reigned for only eleven years.[6]

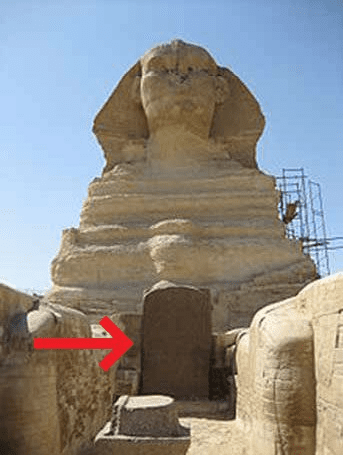

Further evidence that Thutmoses IV who succeeded Amenhotep II, was not his first born and rightful heir comes in the form of the Dream Stele which is positioned between the paws of the Great Sphinx of Giza. It is four metres high with text carved into granite and was erected in the first year of Thutmose IV’s’ reign. It declares a divine justification for him being pharaoh through a dream he had. Obviously, he thought it necessary to justify his position if he was not the first-born son.

This image is curtesy of wilkimedia commons, and the Dream Stele is the dark (granite) stone.

Further, and very powerful evidence for Amenhotep II as being the pharaoh of the exodus, comes from the Egyptian priest Manetho, mentioned previously, who used earlier Egyptian records to obtain his list of pharaohs. He named Amenhotep II as the pharaoh of the exodus.[7]

The Bible provides more information.

Hatshepsut failed to produce a male heir for Thutmoses II. He obtained his heir through a concubine named Iset. Thutmoses III was only two years old when his father, Thutmoses II, died, and Hatshepsut became a female pharaoh as she was Thutmoses I’s daughter. This circumstance brought about a 22 year coregency until Thutmoses III became pharaoh in his own right. She fits in very neatly to being the “pharaoh’s daughter” mentioned in Exodus and in fact she refers to herself on monuments as the “pharaoh’s royal daughter,” despite her father Thutmoses I, being long dead. So quite possibly, this lack of a son may have been the driving force for her being the pharaoh’s daughter who adopted the Hebrew baby she found in a basket floating on the Nile (Exodus 2:5-6).

Hatsheput’s temple is pictured on the right.

More intriguingly, there has been an attempt to erase Hatsheput’s name and image from monuments throughout Egypt. This removal of name and image is the ultimate disgrace to any Egyptian because it would cause that person to cease to exist in the afterlife. It is known as condemnation of memory. However, it fits in beautifully with the exodus narrative of the Bible. Egyptologist, Professor Douglas Petrovich writes,

The responsible individual likely possessed pharaonic authority, and one legitimate motive for Amenhotep II to have committed this act is if Hatshepsut raised Moses as her own son in the royal court (Acts 7:21). After the Red-Sea incident, Amenhotep II would have returned to Egypt seething with anger, both at the loss of his firstborn son and virtually his entire army (Exodus 14:28), so he would have had just cause to erase her memory from Egypt and remove her spirit from the afterlife. The Egyptian people would have supported this edict, since their rage undoubtedly rivaled pharaoh’s, as they also were mourning deceased family members and friends. The nationwide experience of loss also would account for the unified effort throughout Egypt to fulfill this defeated pharaoh’s commission vigorously.[8]

The image below is from Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el Bahri and it shows clearly the chiselled off name of Hatshepsut.

Questions that arise from the biblical account

Did the pharaoh not die with his army in the Red Sea?

The Bible does not say he did. Exodus 14:27-28 states:

Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at daybreak the sea went back to its place. The Egyptians were fleeing toward it, and the Lord swept them into the sea. The water flowed back and covered the chariots and horsemen—the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed the Israelites into the sea. Not one of them survived.

There are other passages in exodus referencing this event, but they only refer to “the Egyptians and pharaoh’s host and do not cite pharaoh specifically.

The same is true for Psalm 106:11 which states: And the waters covered their adversaries; not one of them was left. Again, pharaoh is not mentioned.

Also for Psalm 136:15, the proof text for pharaoh being drowned, says: but [God] overthrew pharaoh and his host in the Red Sea, for his steadfast love endures forever. Petrovich writes:

A cursory reading of the text leads most to believe that because God “overthrew” pharaoh and his army, both parties must have died. However, the Hebrew verb וְנִ֨עֵ֤ר (n’r, “he shook off”) shows that God actually “shook off” the powerful pharaoh and his army, who were bothersome pests that God-whose might is far greater than theirs-merely brushed away. The same Hebrew verb is used in Ps 109:23, where David laments, “I am gone like a shadow when it lengthens; I am shaken off like the locust.”[9]

Petrovich makes clear that the text is not talking about the killing of pharaoh or even his army.

The Hebrew slaves built the city named after Rameses so he must have been the pharaoh at the time.

Exodus 1:11:

So they put slave masters over them to oppress them with forced labor, and they built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for Pharaoh.

An explanation is that the place name Rameses in the text, is called an “anachronism” a more familiar, later term used for a more obscure earlier name. There are other examples of anachronism in the Bible, Genesis 21:14 tells how Abraham provided food and water for Hagar, and with Ishmael she wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba. Beersheba was not a named place in Abraham’s day. Also, Gen. 14:14 says the marauding armies that conquer Sodom and Gomorrah capture Lot and took him with them. When Abraham hears of this, he takes 318 armed servants and pursues them as far as Dan. But Judges 18:29 says the city was originally known as Laish, and it was named Dan after Abraham’s great-grandson Dan.

Summary

- The Bible gives the time of the Exodus as being 1446 BC. Other verses support this date.

- Third century BC Egyptian historian Manetho’s compilation of eighteenth dynasty pharaohs places Amenhotep II as pharaoh at that time. As well, he names Amenhotep II as the pharaoh of the exodus.

- Amenhotep II complies with the two basic biblical requirements for the pharaoh of the exodus; his predecessor must have ruled for more than 40 years and his first-born son did not succeed him as pharaoh since he would have died in the last plague.

- Further evidence that Thutmoses IV who succeeded Amenhotep II, was not his first born and rightful heir comes in the form of the Dream Stele which states that Thutmoses IV had divine approval of his legitimacy as pharaoh. This vindication would not have been necessary if he was the first-born son.

- There has been an attempt to erase Hatsheput’s name and image from monuments throughout Egypt. Hatsheput did not have a son and she fits nicely into being pharaoh’s daughter who took baby Moses as her son. After God working through Moses to bring the ten plagues on Egypt it is easy to understand why Amenhotep II would want her image eradicated completely.

Conclusion

Only Amenhotep II ticks all the boxes for being the pharaoh of the exodus, other pharaohs are decisively eliminated.

Since grave robbers were only interested in the treasure the Egyptian tombs contained, the mummified pharaohs were left. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo has a special place which contains the remains of pharaohs. When we look at the face of Amenhotep II (pictured) we can be quite sure that it is the same face that Moses looked at.

[1] The NIV Study Bible, The Zondervan Corporation, 1985, page 480.[2] Wikipedia.

[3] Egypt History & Civilization, OSIRIS, ISBN 978-977-469-008-2, page 16.

[4] Ancient Egyptian online. https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/manetho.

[5] https://exegesisinternational.org/pdf/ExodusPharaohArticle.pdf.

[6] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ramses-II-king-of-Egypt.

[7] Christopher Eames, Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus? Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology, March-April 2023, Let the Stones Speak Magazine Issue.

[8] D. Petrovich, Amenhotep II and the Historicity of the Exodus Pharaoh. Spring 2006 issue of the Master’s Seminary Journal. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/exodus-from-egypt/3147-amenhotep-ii-and-the-historicity-of-the-exodus-pharaoh.

[9] Ibid.