When Hawaii became America’s fiftieth state of the US in 1951, Hawaiians nominated two historical figures to be commemorated in statue form to be kept in the US Capital in Washington DC. Of the two heroes they settled on, one was not actually Hawaiian but a nineteenth century Belgium missionary. He was Father Damien, the priest of Molokai. April 15, the day of his death, has been declared Father Damien Day in Hawaii.

- In January 1936, at the request of King Leopoid III of Belgium, Damien’s body was returned to his native land in Belgium and he was buried in Leuven, the historic university city close to the village where he was born.

- In 2005, secular Belgium voted him “Greatest Belgium” of all time.

- Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote a 6,000-word defence of him after he was criticised.

- Mahatma Gandhi said that Father Damien’s work had inspired his own social campaigns in India.

- A film about his work, titled; Molokai: The Story of Father Damien, was released on March 15, 2008.

Who was Father Damien and what did he do to get such accolades?[1]

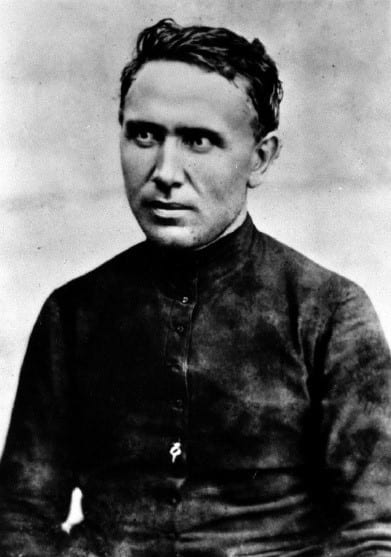

Joseph de Veuster, was born January 3, 1840, in Tremelo, Belgium. He left school at the age of thirteen to work on the family farm and from a young age was known for his boundless energy and physical hardiness. He was determined to become a priest like his older brother; in fact, he was not even fully ordained as a priest when his brother fell ill with typhus and Damien volunteered to go in his place on mission to Hawaii. In spite of the disapproval of his superiors, he set out on the five-month voyage to Honolulu in October 1863.

Joseph de Veuster, was born January 3, 1840, in Tremelo, Belgium. He left school at the age of thirteen to work on the family farm and from a young age was known for his boundless energy and physical hardiness. He was determined to become a priest like his older brother; in fact, he was not even fully ordained as a priest when his brother fell ill with typhus and Damien volunteered to go in his place on mission to Hawaii. In spite of the disapproval of his superiors, he set out on the five-month voyage to Honolulu in October 1863.

In 1873, the young priest was visiting Maui for the consecration of a large church where he heard the local bishop speak of the wretched conditions at the leper colony on Molokai. It was too much to ask a priest to live there permanently, but he was looking for missionaries who were willing to visit on rotation, three months at a time. Damien immediately put up his hand and on Saturday May 10, at the age of thirty-three, he went to the island; arriving with perhaps 50 lepers who knew well they would never return to those they had left behind. Damien, too, had written before leaving that he had a strong feeling he never again would depart from there, and it was during his first week in the colony that he wrote to urge the need for a permanent priest: Please send me…. I would like to sacrifice myself for the poor lepers.

It was an astonishing request. Molokai was in 1873 reputed to be a hellhole. Of the approximately 500 residence, many were in the final stages of the disease, with limbs and faces horribly maimed, covered in festering sores and lumps that gave off an overpowering smell. Someone would die every day and those with enough strength remaining might wrap them in the foul blanket they had been lying on and carry them off to be buried. If the graves were not deep enough, wild pigs would root up the corpses overnight and eat the rotting flesh, adding to the stench of the settlement. It was a place of hopelessness where substance abuse and sexual exploitation was ripe.

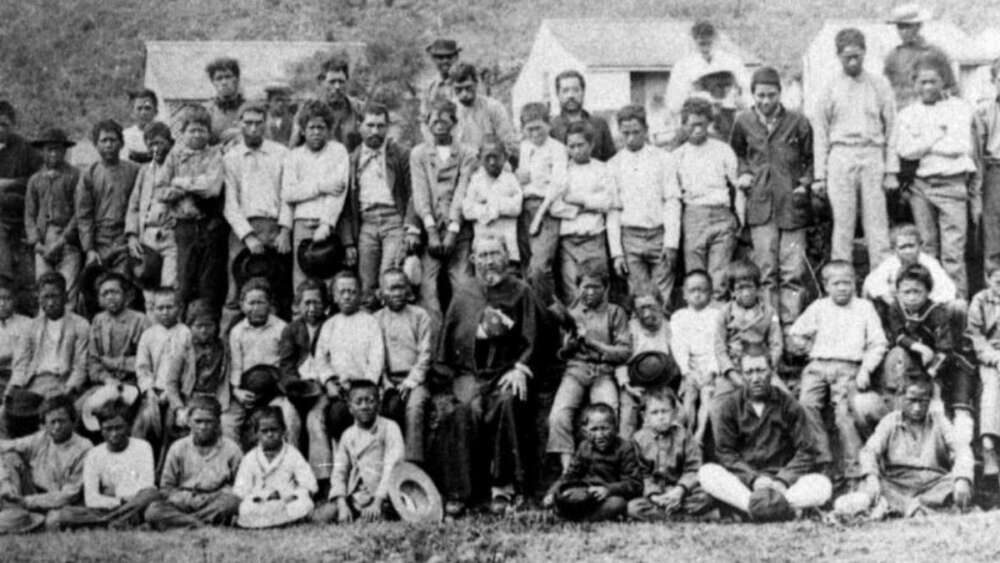

Although he was advised not to touch them or eat with them, how could he not? He showed the love for them that his master Jesus did when he dealt with lepers. He found their mutilations and their odour repulsive but he set aside his visceral response. He never hesitated to touch the lepers, he blessed the dying, embraced the sick, ate from the same pot as the sufferers and even shared his pipe with them. He built coffins and dug graves in the rocky volcanic ground of the peninsula. He built a fence around the cemetery by the church to keep the pigs out. He built shelters for the lepers and laid pipes to ensure a clean water supply. He not only became a spiritual guide for the colony but also a carpenter, magistrate, cook, physician, gardener, and schoolteacher. He encouraged those still able to work giving them a sense of purpose.

Also, he introduced music to the community, forming leper choirs and bands. Piano pieces for one would be played by two children, who would have enough fingers between them. He paid special attention to children who arrived each year, torn from their parents, knowing they were especially vulnerable to neglect and abuse. He built orphanages and schools for both boys and girls.

He brought dignity to the residents’ lives and also to their deaths, arranging a proper funeral for each and every member of the colony. Up to a quarter of the population; 150-200 people would die each year. They would be replaced by freshly symptomatic sufferers. The battle he fought was against meaninglessness and despair as much as against the disease itself; he assured the people that they were valuable in the sight of God and that death was not the end.

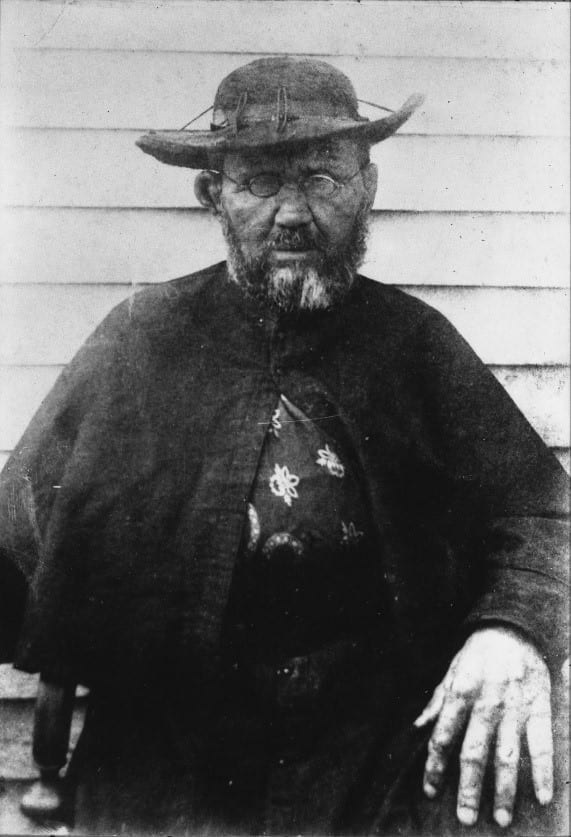

Father Damien’s own leprosy

It was during the year 1884, more than a decade after he came to live among the lepers of Kalaupapa, that Father Damien’s symptoms became undeniable. Yellow spots appeared on his back and arms. His left foot became increasingly numb. He knew the signs as well as anybody and he also knew what to expect: the great physical pain; the maiming; the obstruction of the vocal cords; the collapse of his facial features – ears swelling to reach perhaps his shoulders, eyelids eventually unable to close, leading to blindness.

It was during the year 1884, more than a decade after he came to live among the lepers of Kalaupapa, that Father Damien’s symptoms became undeniable. Yellow spots appeared on his back and arms. His left foot became increasingly numb. He knew the signs as well as anybody and he also knew what to expect: the great physical pain; the maiming; the obstruction of the vocal cords; the collapse of his facial features – ears swelling to reach perhaps his shoulders, eyelids eventually unable to close, leading to blindness.

The depth of his faith can be ascertained from one of the letters he wrote to his superiors in Hawaii:

Those microbes have finally settled themselves on my left leg and my ear, and an eyebrow begins to fall. I expect to have my face soon disfigured. Having no doubt myself of the true character of my disease, I feel calm, resigned, and happier among my people. Almighty God knows what is best for my satisfaction, and with that conviction, I say daily a good fiat vulantas tua—your will be done.

In one of his last letters he wrote, my face and my hands are already decomposing, but the good Lord is calling me to keep Easter with Himself.

Father Damien died on April 15, 1889 and then was laid to rest under the same pandanus tree where he first slept upon his arrival on Molokai. Above his grave his friends set a black marble cross with the inscription, Damien de Veuster, Died a Martyr of Charity. His body was reburied in Louvain, Belgium in 1936 at the request of King Leopoid III of Belgium.

Note the first photo of Father Damien was taken in 1873, the year he went to Molokai. The photo above was taken just 26 years later.

Why?

Why would someone spend his life helping people who had the most feared of all diseases and knowing full well that he too, will be a victim to its degrading finale after years of suffering? Father Damien understood that all people were important to God and his desire was to reach out to the those who had been cast out of society just as Jesus did.

With his love for the people and his dedication to God, Father Damien did what he saw was his duty despite the personal consequences.

Conclusion

Sixty-six artists bid for the commissioned project of creating a statue of Father Damien. Only seven were selected to be reviewed by the Hawaii’s State Statuary Hall Commission. Marisol Escobar, a New York City sculptor, won the bid. Commission members favoured the contemporary feel and look of the Escobar design as opposed to the classical representations of Father Damien that others submitted. Her statue was based on a photo she saw of him near the end of his life, which is why he is wearing glasses and has his arm in a sling

Sixty-six artists bid for the commissioned project of creating a statue of Father Damien. Only seven were selected to be reviewed by the Hawaii’s State Statuary Hall Commission. Marisol Escobar, a New York City sculptor, won the bid. Commission members favoured the contemporary feel and look of the Escobar design as opposed to the classical representations of Father Damien that others submitted. Her statue was based on a photo she saw of him near the end of his life, which is why he is wearing glasses and has his arm in a sling

Note 1. Leprosy is caused by infection with the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. It mainly affects the skin, eyes, nose and peripheral nerves. Symptoms include light-coloured or red skin patches with reduced sensation, numbness and weakness in hands and feet. Leprosy can be cured with 6-12 months of multi-drug therapy. Early treatment avoids disability.

Note 2. To watch an excellent short video regarding Father Damien which shows the place where he worked with the lepers, click here

Note 3. All images are from Wikimedia commons with gratitude.

[1] Tis section is largely taken from Natasha Moore’s book, For the Love of God, Centre for Public Christianity, 2019, pages 197-198. She states that a lot of her information is from Jan de Volder, The Spirit of Father Damien: The Leper Priest – A Saint for Our Times. Translation by John Steffen, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2010, page 39.